Over the last few years climbing has become more widely known as a sport and leisure activity. The rise of indoor climbing gyms and the accessibility of bouldering, which requires less equipment, have created easier routes for people to get into the sport. One of the best things about this boom is seeing the diversity of human beings that take to the wall. The idea that most people can climb is proudly shouted by enthusiasts trying to convince a friend to hop on the wall – “It doesn’t matter how tall you are! You don’t have to have huge muscles! Anyone can try it!”. More and more I hear people expressing how safe and accessible it feels for members of every sex, as climbing gyms veer away from the macho culture often found at other gyms or in different sports.

It’s been encouraging to witness the changes over the years. When I first started climbing, back in those hazy golden days of Highball (when the training area was a couple of hang bars in place of the squad wall), things felt a little different. Climbing was still a fairly niche sport and I was in a minority of female climbers. Considering I was a casual climber at best, I can’t say I really balanced anything out. There was a small crew of dedicated female climbers but they were outnumbered by packs of hardcore climber dudes. From personal experience, no matter how often I silently repeated the mantra ‘climbing is for everyone’, I’ll admit to being intimidated at the idea of falling in front of a bunch of burly blokes, no matter how friendly they appeared to be; I felt an unspoken societal expectation that my body would be less capable (not to mention the mere fact of being a woman in the centre made you a beacon for unwanted attention). To the female climbers back then, I give the chalkiest of salutations, for they were not put off by the beta spraying boulder bros. I would tentatively suggest that the predominance of men on the wall, both at Highball and in the general climbing world, could have some link to cultural associations of masculinity with adventure and risk taking. Historically, as an extreme sport that started outdoors, access for women would have been much harder, given that the dangerous pursuits were not considered particularly feminine. We have only to look at the example of the ascent of the Grepon by Miriam O’Brien Underhill and Alice Damesme in 1929 – this achievement did not improve the status of female climbers, but instead had the opposite effect of reducing the status of the climb according to one particular mountaineer who stated “The Grépon has disappeared. Now that it has been done by two women alone, no self-respecting man can undertake it. A pity, too, because it used to be a very good climb.”

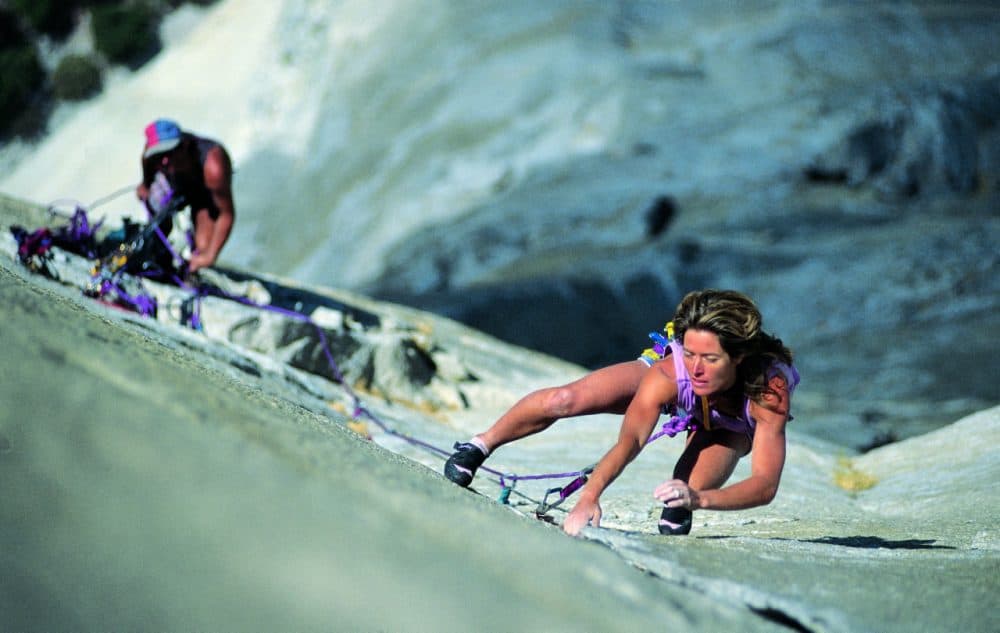

Despite this, it is clear that female climbers can crush just as hard as anyone. In the world of professional climbing, there are countless stories of those who have pushed boundaries in the sport, not only as ‘female climbers’, but simply as climbers. In 1993, Lynn Hill famously free-climbed the Nose before any of her male counterparts, declaring on completion “It goes, boys”. Even amongst amateurs in my tiny community at Highball it was obvious that physical attributes relating to sex were not a barrier.

1.https://www.climbing.com/people/consolidated-history-womens-climbing-achievements/#:~:text=1799%3A%20The%20Beginning&text=Although%20the%20first%20documented%20ascent,in%20the%20Alps%20of%20Savoy.

2.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynn_Hill

This has been backed up by some recent research into the physiology of climbing, which suggests that the small performance gap in climbing compared to other sports could be a result of the evolutionary importance of tree climbing. The development of long arms, a short trunk, and upright posture in all sexes is an indication that as a species we have physically adapted to climbing for survival. The research proposes the idea that ‘movements with a greater degree of evolutionary importance’ are more common to sports with greater equality among the sexes. There is still much to discover in this area but initial findings are interesting, and reflect what many of us already already witness both indoors and out. Essentially, when we climb we are tapping into basic survival skills that are equally important across the sexes.

This is not to say that our bodies are all equally capable in exactly the same way, but that each discipline of climbing offers a variety of problems, and requires such a range of movements that everyone can find something to suit. Where someone might struggle more on a balancey slab route, they will find themselves easily swinging about on a steep overhang. This also encourages some wild creativity as each person finds their own solution! As the popularity of the sport grows I am so happy to find an ever more diverse crowd both indoors and outdoors. At Highball, there has been a huge increase in climbers who do not fit the strong man mould. Their perseverance over the years, coupled with the growth of the sport as a whole, has inspired others to get involved and the space feels like it is genuinely growing in inclusivity for different bodies. As we move forwards I will continue to explore this topic and try to highlight the incredible achievements of female climbers who have broken barriers for the rest of us.